Marlowe, Shakespeare, and the Ashford Cage

Marlowe's local knowledge argues for his authorship of the Jack Cade scenes of Henry VI Part 2.

Original Peer-Reviewed Article

First published in Notes & Queries, Oxford Academic1

The New Oxford Shakespeare’s attribution of parts of Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part 2 to Christopher Marlowe, however contentious the methods might be, follows a long history of scholars attributing the play’s forerunner, The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Famous Houses of Yorke and Lancaster to Marlowe.

Edmund Malone was inclined to believe ‘that Marlowe was the author of one, if not both’ of the two early Henry VI plays, an opinion shared by Hallam, Dyce, Fleay, Swinburne and Tucker Brooke.2 There are traditional literary/linguistic reasons why we might consider that Marlowe had a hand in 2 Henry VI, and particularly the Jack Cade scenes that comprise most of Act 4.

The efficacy and reliability of the stylometric methods underlying the New Oxford Shakspeare attributions are currently under review.3 This is not surprising, given that their results are not unanimous, and sometimes conflicting. Segarra et al’s Word Adjacency Networks method gives Act 4 of 2 Henry VI to Shakespeare, though the authors admit ‘except for Act 4 scene 10, our method cannot clearly distinguish between Marlowe and Shakespeare in this part of the play’. Craig and Kinney’s tests appear to show that the Jack Cade scenes were by Marlowe rather than Shakespeare.4 All twelve of their tests (analysing both function and lexical words) detected Marlowe’s style in scenes 4.3 to 4.10. Seven out of the twelve (chiefly function word but not lexical word tests) detected Marlowe in scene 4.2, where the Jack Cade sequence begins.

Yet there seems no reason why, if Marlowe wrote the Cade sequence, he did not write all of it. There is a previously unnoticed detail in Act 4 Scene 2 which adds to the argument that Marlowe had a hand in it, even if some stylometric tests cannot detect it.

In this scene it is said of Jack Cade that ‘his father had never a house but the cage’.5 The word ‘cage’ is glossed by Shakespeare's modern editors as ‘a pen, lock-up, small prison compound’. But in all the versions of the play published up to and including 1623, the word is capitalised: ‘his father had never a house but the Cage.’ Although nouns are often capitalised in Elizabethan texts in a manner that modern eyes might regard as haphazard, they are also capitalised (as now) when they are proper nouns, which raises the possibility that a specific place was being referenced. If it was, that specific place would be in Ashford. Though Shakespeare's sources state that Jack Cade was an Irishman, the author of this scene made him ‘a headstrong Kentishman, John Cade of Ashford’, a change that is hard to explain from the standpoint of Shakespeare authoring this scene.6 The man who speaks the line about 'the Cage' is, in the Folio version, 'Dick, the butcher of Ashford'.

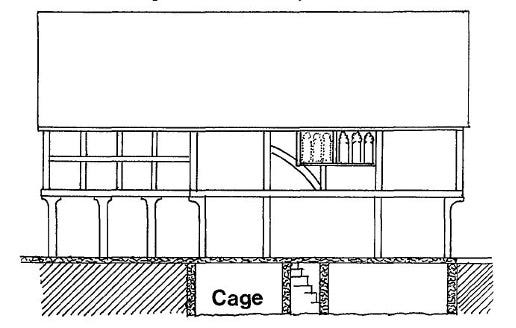

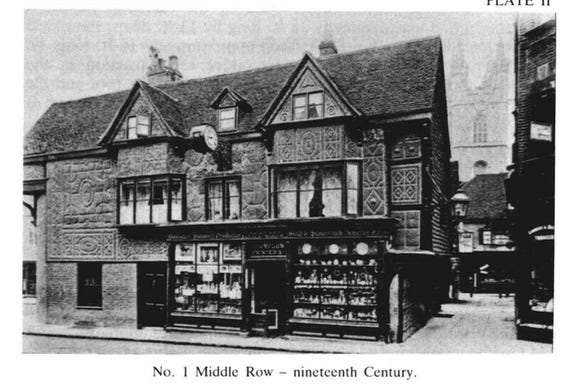

Sheila Sweetinburgh writes that ‘The building referred to as the ‘Cage’ in fifteenth-century Ashford appears to have been a market or a court hall’.7 She references an article by W.R. Briscall, describing the discovery of the Ashford Cage, and the archaeological survey of the building that contained it.8 This building, Ashford’s market hall, doubled as a court. The Cage was small cell (8ft long, 4ft wide and 6ft high) underneath Ashford’s market hall where local troublemakers, such as drunks, would be locked up overnight.

It is hard to imagine a reason why Shakespeare would have gone against the historical sources to make Cade a Kentishman, placing him and his followers specifically in the town of Ashford. Nor is there evidence that the Ashford Cage was so notorious, outside the bounds of Kent, that Shakespeare would think to write this local reference into the mouth of ‘Dick the butcher of Ashford’. It seems perfectly explicable, however, if it were Canterbury-born Marlowe who wrote this scene.

Additional Images for your interest (from Briscall):

Rosalind Barber, 2 Henry VI and the Ashford Cage, Notes and Queries, Volume 66, Issue 3, September 2019, Pages 409–410, https://doi.org/10.1093/notesj/gjz063

A more comprehensive list of early scholars who gave the early versions of the two Henry VI plays to Marlowe is given in Vol. II of John Edwin Bakeless, The Tragicall History of Christopher Marlowe., 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1942), 224-25.

Pervez Rizvi, "Authorship Attribution for Early Modern Plays Using Function Word Adjacency Networks: A Critical View," ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews (2018), Pervez Rizvi, "The Interpretation of Zeta Test Results," Digital Scholarship in the Humanities fqy038 (2018), David Benjamin Auerbach, "Statistical Infelicities in the New Oxford Shakespeare Authorship Companion," ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews (2019), Darren Freebury-Jones and Marcus Dahl, "The Limitations of Microattribution," Texas Studies in Literature and Language 60, no. 4 (2018).

D. H. Craig and Arthur F. Kinney, Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 70-74.

The First Part of the Contention, 4.2.53, in William Shakespeare et al., eds., The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Clarendon, 2005), 79.

Contention, 3.1.356-7, 72.

Sheila Sweetinburgh, Later Medieval Kent, 1220-1540, Kent History Project (Martlesham: Boydell Press, 2010), 146, n.57.

W.R. Briscall, "The Ashford Cage," Archaeologia Cantiana 101 (1984).

Interesting, from an architectural standpoint. Also...cage/cade